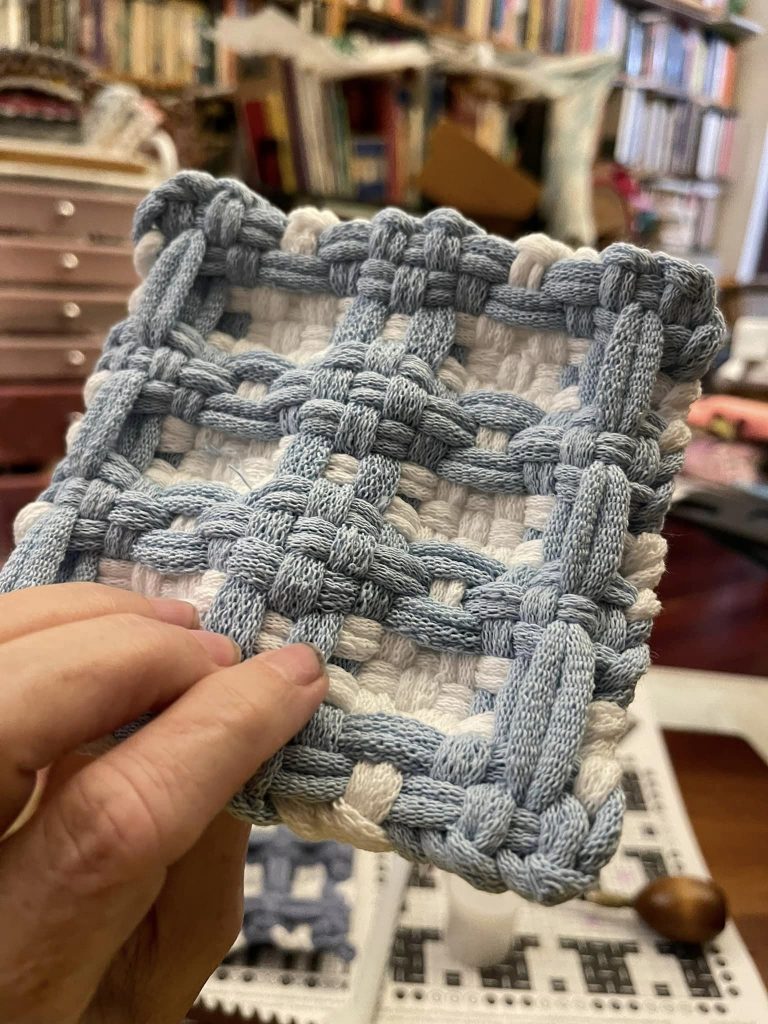

Experiments in classical weave structures continue with Overshot!

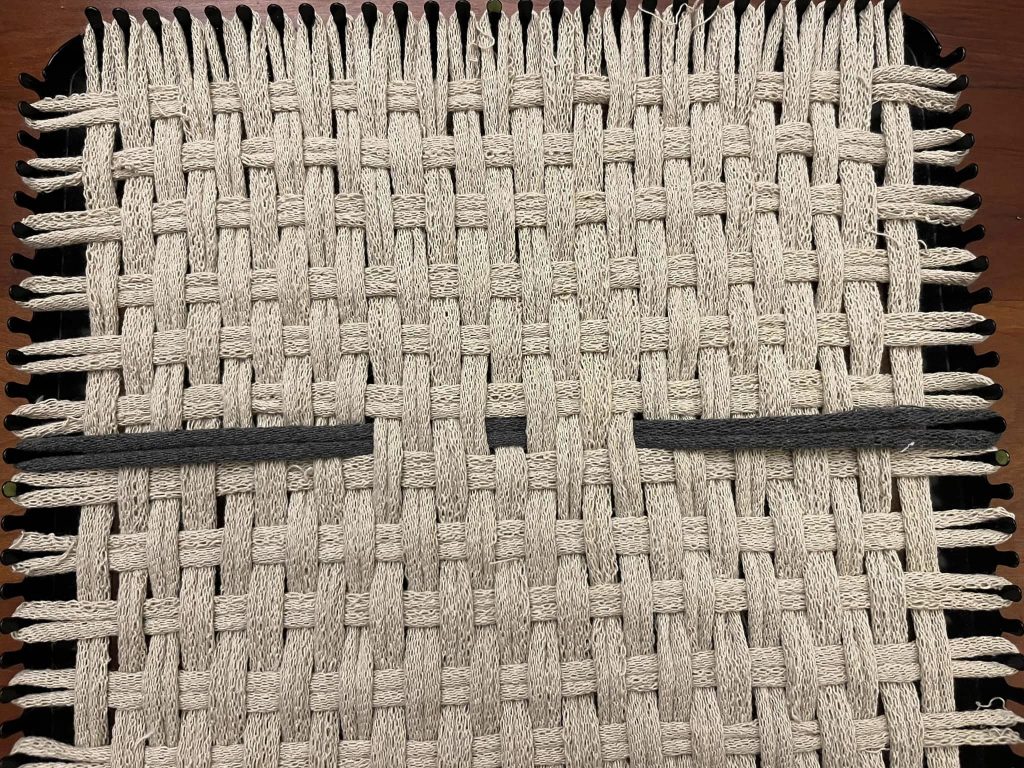

This fabric has a base plainweave (tabby / over-under across each row), with a design pattern overlaid on it, created by rows with long floats. The design pattern appears to float on the surface.

This one is adapted from the Swedish Halvdräll style, in honor of which I chose flax and willow Harrisville loops. The result is textured, cushy, with tabby sections drawn up into pillow layers by the alternating longer floats on their surface.

To highlight the structure for my (and your, since I remembered to take photos!) understanding, I wove starting with the base tabby layer, using all the column pegs, and every other (even) row peg.

Having established that plainweave fabric, I then took my dozen willow loops, and wove them into the base fabric according to the pattern. You may observe that adding the new loops forced floats where there had previously been simple over/unders in the columns. Those smaller floats help pinch the longer floats in the rows into patterns on the surface, and pull the fabric along their length.

For the last 2 rows (top and bottom), instead of the design pattern as charted, I decided to plainweave (tabby / over-under across the row) both rows, to flatten the edge for a more attractive bindoff and function a bit like a selvage. (Chart update pending.)

I am curious if I could shift the plainweave rows now at the top & bottom of the entire chart (1 and 27) to be in between color row changes (new rows 9 and 19, respectively), so the surface floats could be pinched towards each other in 2×2 bundles (like the center section), instead of the 1x2x1 pinch we are getting in the top and bottom sections right now…