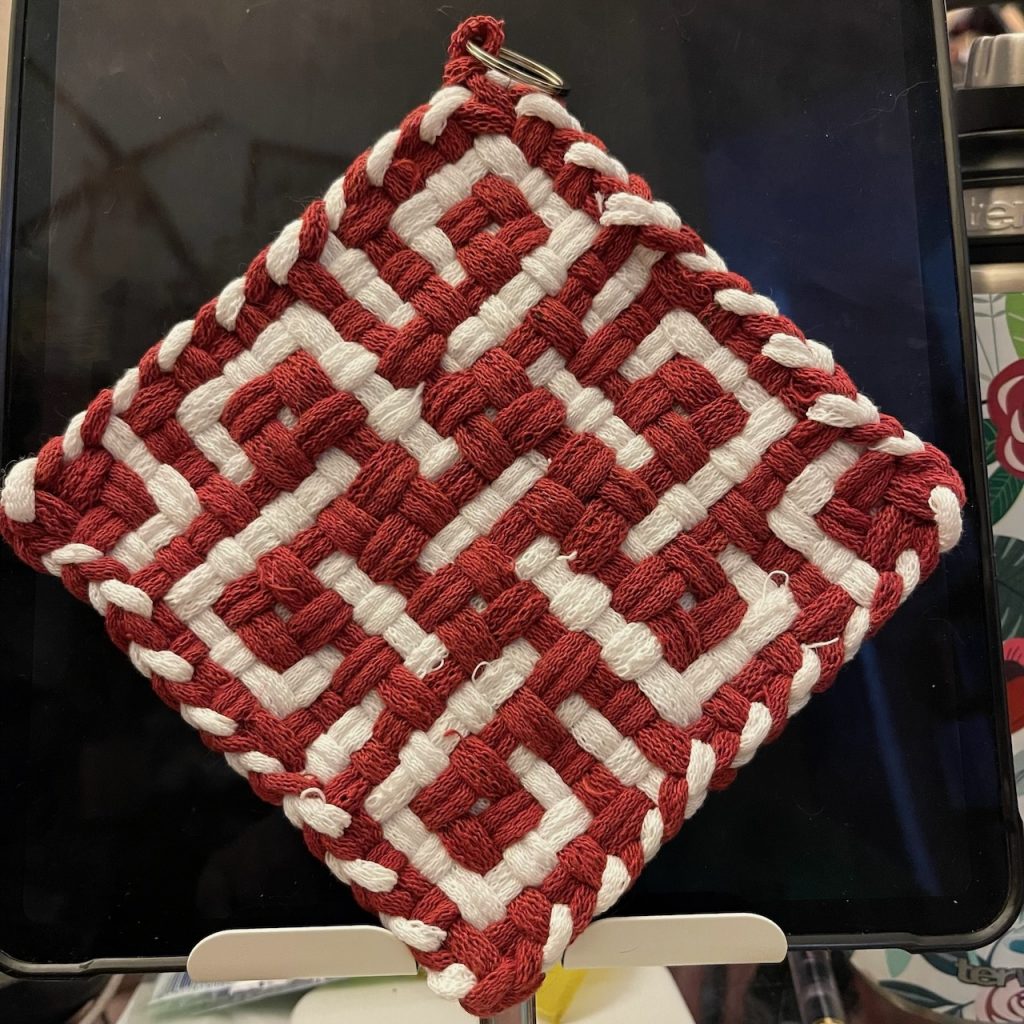

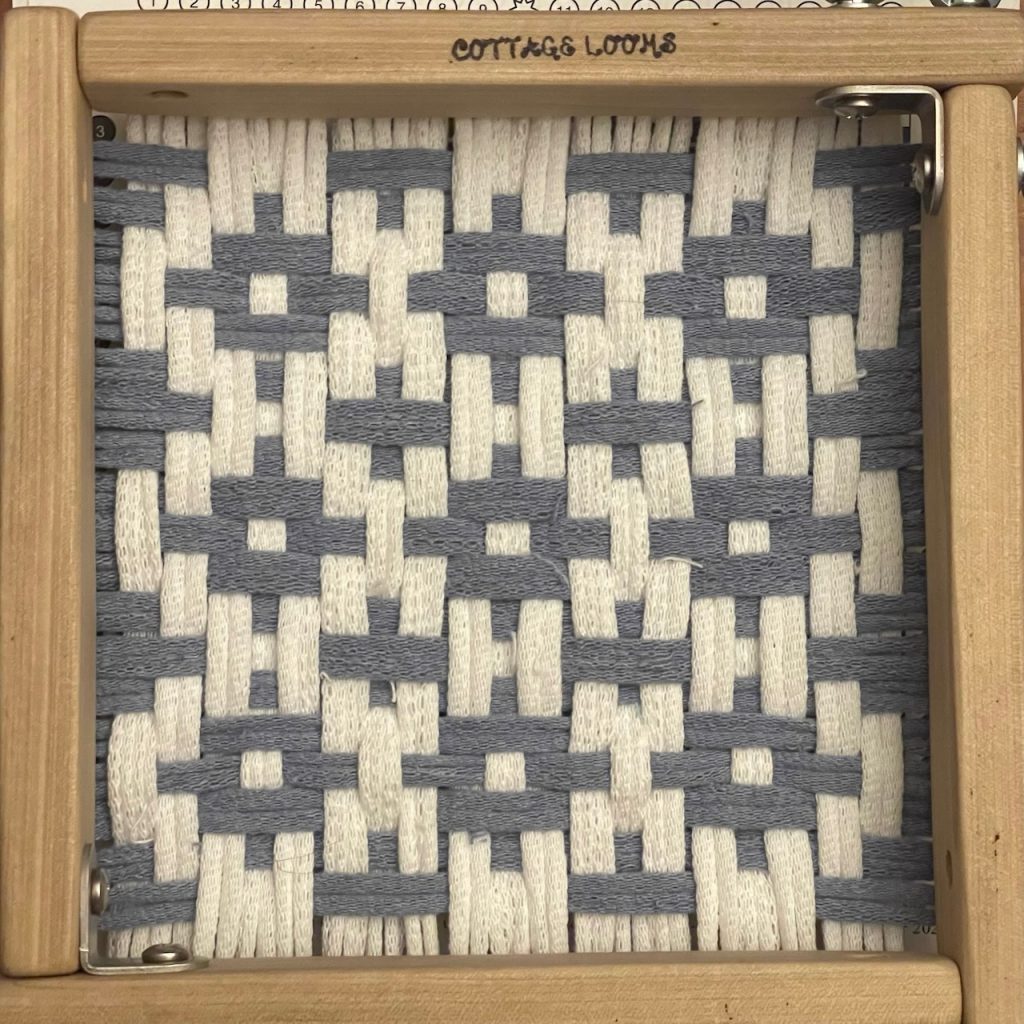

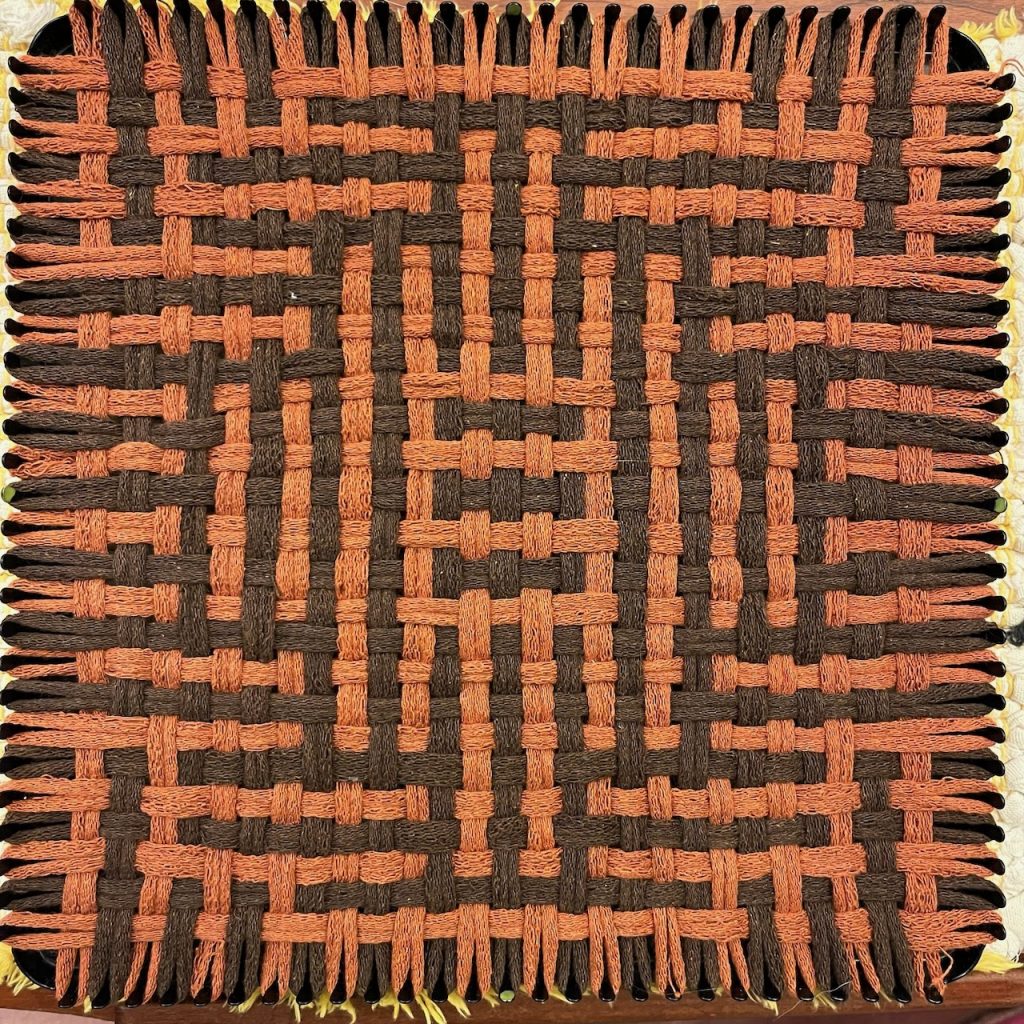

Okay, this is fun! Inspired by the background weave pattern on the “Outstanding in her field” potholder I wove this morning, I whipped up a sample with just that weave throughout. It’s a 1/2 basketweave, by which I mean over-2/under-2 across the row, then shift 2 columns to weave over-2/under-2 across the next row. (See photos on the loom, below.)

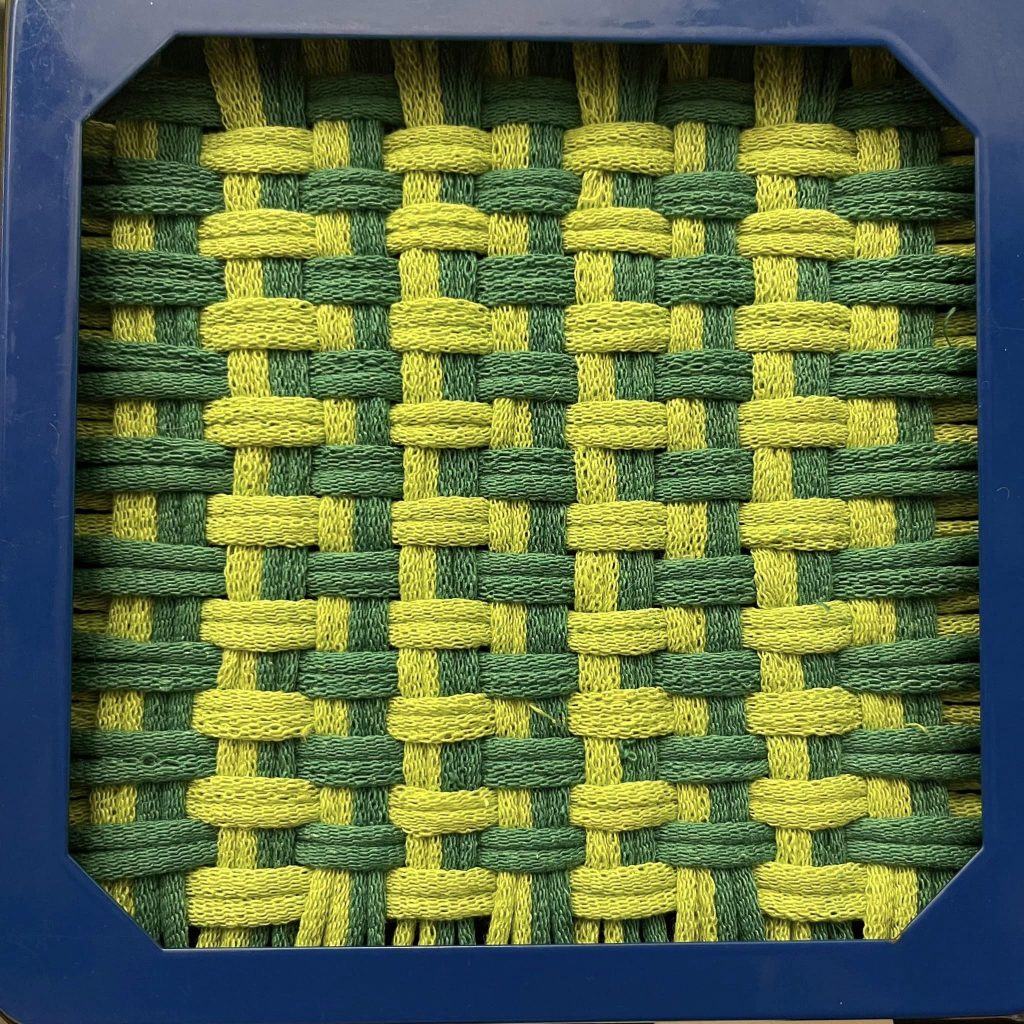

Love the “teeth” of the green & lime potholder, which uses a 1/1 alternating color sequence for both rows and columns.

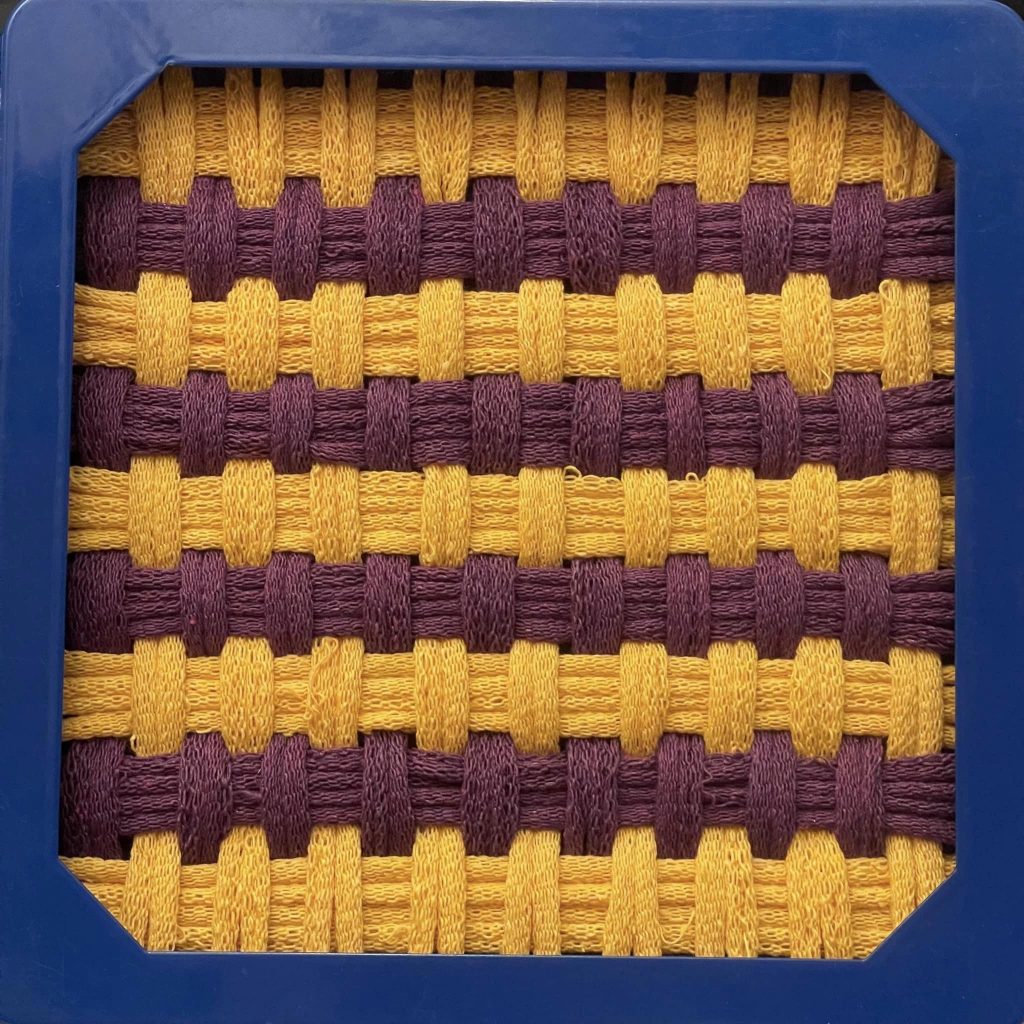

The yellow & plum potholder is the exact same weave pattern using a threading pattern alternating colors 2/2 for columns and 1/1 for rows. (That will make more sense when you look at the on-loom photo, I promise!)

The outcome is distinctly ribbed and gently textured, but flat overall with no significant lumps. Very bendy, with little skew.

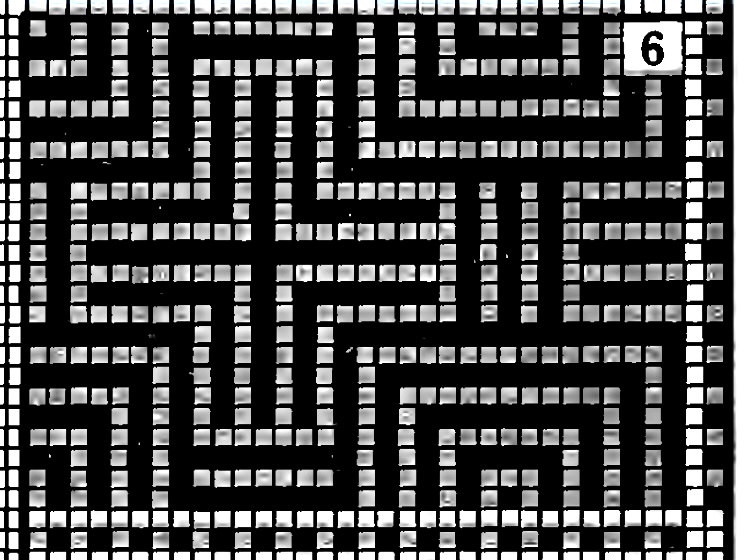

[Click for charts for Half Basketweave Stripes and Half Basketweave Combs]